A team of researchers from the U.S. and India has developed a powerful new sensor that can identify dangerous levels of iron in water faster, cheaper, and with far greater accuracy than existing methods. The project was led by Fei Yan, professor at North Carolina Central University (NCCU). Yan is also part of the NSF PREM for Hybrid Nanoscale Systems.

The collaboration—funded by NSF and the U.S. Army Research Office—brought together experts in chemistry, materials science, and computer modeling from NCCU, Pennsylvania State University, and IIIT Bhopal. Postdoctoral fellows Amit Kumar Shringi and Rajeev Kumar, along with Rajneesh Chaurasiya and PhD student Justin Lin, played key roles. They recently published their research in the journal Nanoscale.

Why This Matters

Toxic iron (Fe³⁺) from industrial waste can seep into water supplies, leading to serious health issues such as anemia and organ damage, as well as environmental problems like fish kills and algal blooms. Current lab tests are either too slow, too expensive, or too cumbersome for use in the field.

How It Works

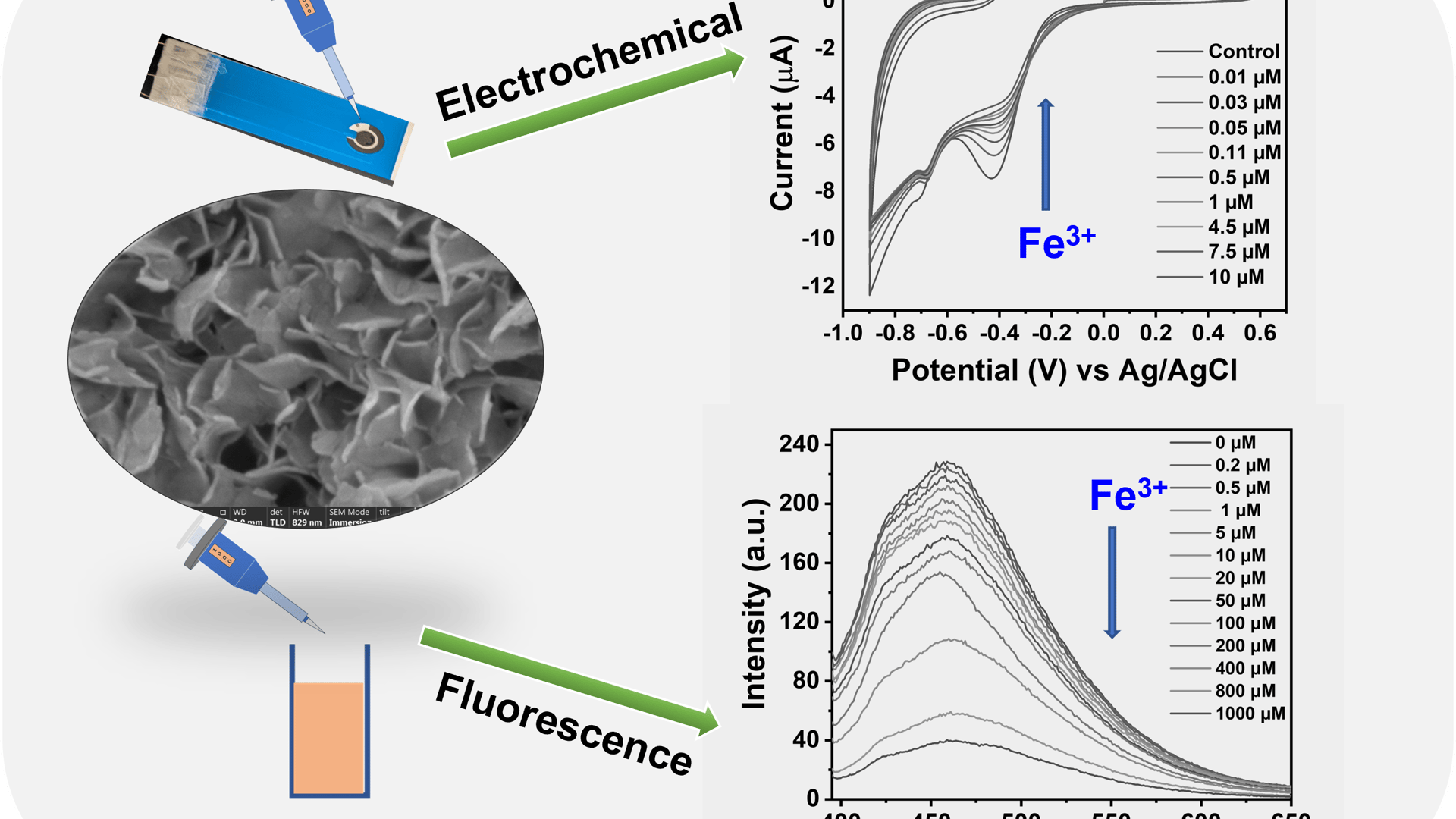

The team’s new material, called Bi₂O₂Se nanosheets, allows the sensor to work in two different ways:

Electrochemical mode detects iron at ultra-low levels—down to just 10 nanomolar.

Fluorescent “turn-off” mode detects iron at concentrations as low as 110 nanomolar, beating most sensors reported so far.

Importantly, the sensor can tell iron apart from other metals like lead or mercury. Computer models showed that iron binds much more strongly to the nanosheets, explaining the sensor’s accuracy.

A First in Materials Science

“This work demonstrates how emerging non-van der Waals 2D materials like Bi₂O₂Se can bridge the gap between advanced nanoscience and real-world environmental monitoring—offering a low-cost, highly sensitive, and portable solution for detecting toxic metal ions crucial to human health and ecosystem stability,” says Yan. What’s more, this is the first time a non-traditional, non-van der Waals 2D material has been used in a dual-mode environmental sensor. The result: a low-cost, portable tool that could one day make real-time water quality testing accessible to communities worldwide.